David Inserra

This Independence Day, it is worth celebrating the freedom of speech we enjoy, especially in light of recent events in Europe. In the UK, a man was found guilty of public disorder for the peaceful protest and burning of a Quran outside the Turkish embassy; two men assaulted the man during the protest. In Germany, the country held its 12th national “day of action against hate posts,” featuring 6:00 am police raids at dozens of addresses across Germany. The US’s history with free speech hasn’t been (and still isn’t) perfect, but it’s still worth celebrating the way that Americans can express disfavored views that are censored elsewhere.

In the American colonial period, criticism of political leaders was often criminalized under seditious libel laws. Thankfully, Americans detested these laws and, as seen in the lead-up to the revolution, often used colorful language and insults, as well as some misleading information, to stoke opposition to British rule. And so when instituting a new Constitution, the founders codified this belief in free expression in the First Amendment.

Now this commitment faced immediate challenges, including in the American South, where states established what were in effect hate speech laws to prevent criticism or incite hatred of slavery or slave owners. Women suffragettes were arrested outside the White House for burning an effigy of President Wilson and claiming he held millions of women in political slavery. Hateful or offensive speech was still repressed until the Supreme Court affirmed a more complete view of the First Amendment that our society enjoys today.

But that’s not the road taken by most of the rest of the world. Instead, many continue to hold the view that hateful and offensive speech is a danger that must be suppressed. Indeed, the seriousness with which Europe takes “hate speech” would suggest that they view it as a major threat on par with physical violence. Take, for example, a recent statement by the Secretary General of the Council of Europe that “hate speech is a challenge to democracy itself” and that “hate speech and hate crime are not separate problems.”

But while society may rightly frown upon hateful and offensive speech, there are multiple problems with viewing hate speech as a problem the state can police. First is the perennial question: hate speech as defined by whom? Hamit Coskun, the man who burned the Quran in front of the Turkish embassy, did not believe he was being hateful but was engaging in a legitimate protest, but those two men who assaulted him clearly felt it was hateful. And indeed, the judge relied on the violence and hostility of those men as evidence that Coskun’s speech was hateful and disorderly.

Hate speech is an inherently vague concept, and so any attempt to criminalize it will ultimately place a great deal of power over the speech rights of citizens in the hands of the government or in the hands of the loudest and most aggressive parts of society that cannot handle speech they find offensive and blasphemous.

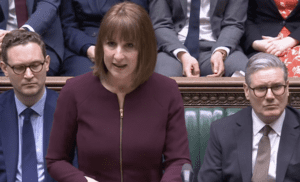

Second, hate speech laws will inevitably infringe on political speech and democratic debate. Coskun has clearly stated that his protest was on account of Turkey’s Islamist slide toward authoritarianism under President Erdogan. As an atheist of Armenian and Kurdish descent, Coskun believed deeply in the secularism of the modern Turkish state as implemented by its founder, Kemal Atatürk. And he has paid a price for his beliefs, being arrested in Turkey and losing family members on account of his activism. His protest was designed to highlight the government forcing its view of religion on society and the use of force against those who resisted. But the UK prosecutors and judge believed his actions were “motivated at least in part by hatred of followers of the religion.” So his political speech was punished.

Similarly, speech that is critical of politicians has been increasingly targeted by German laws against offending others. One journalist created a satirical meme of former Interior Minister Nancy Faeser holding a sign that read “I hate freedom of opinion,” only to be found guilty of abuse and defamation of a political figure. Individuals calling the former chancellor Angela Merkel a “stupid slag” have been prosecuted, and photoshops calling former Green Party Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck a “dunderhead” result in police raids and confiscated devices. Yes, this speech is crude, and some of this speech is even more offensive. But the German government’s power over speech is silencing core political speech, as the number of hate and offensive speech prosecutions has soared from 2,411 in 2021 to 10,732 in 2024. The result is that Germans increasingly feel unable to express their opinions, with multiple polls finding around 44 percent of Germans expressing such concerns, up from 16 percent in 1990. In short, hate speech laws are not saving democracy; they are weakening it.

And this, of course, leads to the ultimate problem: hate speech laws aren’t very effective at countering hateful ideas and may even make things worse. Censoring speech that many view as hateful doesn’t convince those who hold the hateful ideas that their views are wrong. Rather than convincing such people with words, censorship uses the brute force of government punishments. While some individuals may find such force convincing, many others may harden their views.

And by not giving people the ability to hotly criticize leaders, ideas, and institutions in society, government may be removing the safety valve such speech offers. Free speech allows good ideas to challenge bad ideas and gives people with grievances, whether real or just perceived, the opportunity to air their anger. In a world of hate speech laws, those speakers cannot use their words to express their frustrations and may instead turn to increasingly extreme measures. Research suggests that democracies with greater protections for speech have less social violence and unrest.

And at a more practical level, free speech allows people to understand exactly what each other believes. Aren’t we all better off knowing if our fellow citizens and neighbors hold truly despicable ideas rather than forcing them to go underground with their secret beliefs?

In short, censoring hate speech allows the government to arbitrarily silence speech disfavored by the government or powerful groups that often address significant political and social topics. Censorship is also a poor tool for changing the minds of those with hateful ideas, instead pushing them deeper underground and potentially towards more extreme beliefs and actions.

As Europe continues to escalate its war with hate speech but with no victory in sight, we should be thankful that we do not live under such laws here at home. And this should renew our commitment to defending free expression for all, regardless of our political party.