Alex Nowrasteh

Darel E. Paul, the Willmott Family Third Century Professor of Political Science at Williams College, wrote a piece for Compact Magazine titled “Mass Immigration Lowers Fertility.” He uses the example of Czechia to argue that a surge of refugees from Ukraine lowered fertility. Paul’s piece is unconvincing, even if well-written and interesting. The latter is certainly the case, as it combines my two favorite social science topics: immigration and fertility. However, the analysis leaves much to be desired. Below, I explain the problems with Paul’s analysis and show that the surge of Ukrainian refugees to Czechia likely did not lower the crude birth rate.

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine sent about 5.6 million Ukrainian refugees fleeing abroad, mostly to other European countries. As a percentage of the resident population, the refugees in Moldova comprised 5.1 percent of that country’s population—the highest refugee population share in the sample. Czechia is second at 3.45 percent. Paul is correct that Czechia’s crude birth rate fell after the Ukrainian refugees began to arrive in 2022, but it fell elsewhere at the same time.

Czechia’s birth rate fell from 10.6 per 1,000 in 2021 to 8.4 per 1,000 in 2023, about a 21 percent decline. Only three other countries (Macao, Romania, and Seychelles) in the world had crude birth rates that fell more than Czechia’s. Ukrainian refugees in Romania were less than one percent of its population. During the same time, the crude birth rate fell by about 8 percent in high-income countries, 9 percent in Europe, and 5 percent globally. But Moldova’s crude birth rate only fell about 6.6 percent, from 11.5 in 2021 to 10.8 in 2023.

Thus, Czechia’s birth rate fell more than almost all other countries in the world and a lot more than the one country that admitted more Ukrainian refugees as a percent of its population. There is some evidence for and against Paul’s thesis.

The messy inconclusiveness of the analysis above is why comparison to a proper counterfactual is essential for a rigorous analysis. Comparing current crude birth rates today with the past is insufficient. We need to estimate what would have happened to the crude birth rate in Czechia without the Ukrainian refugees to have any hope of understanding what’s going on. Thus, Paul’s analysis doesn’t allow us to see whether Czechia’s birth rate fell compared to a reasonable counterfactual, nor to speculate about the causes if such a fall did occur.

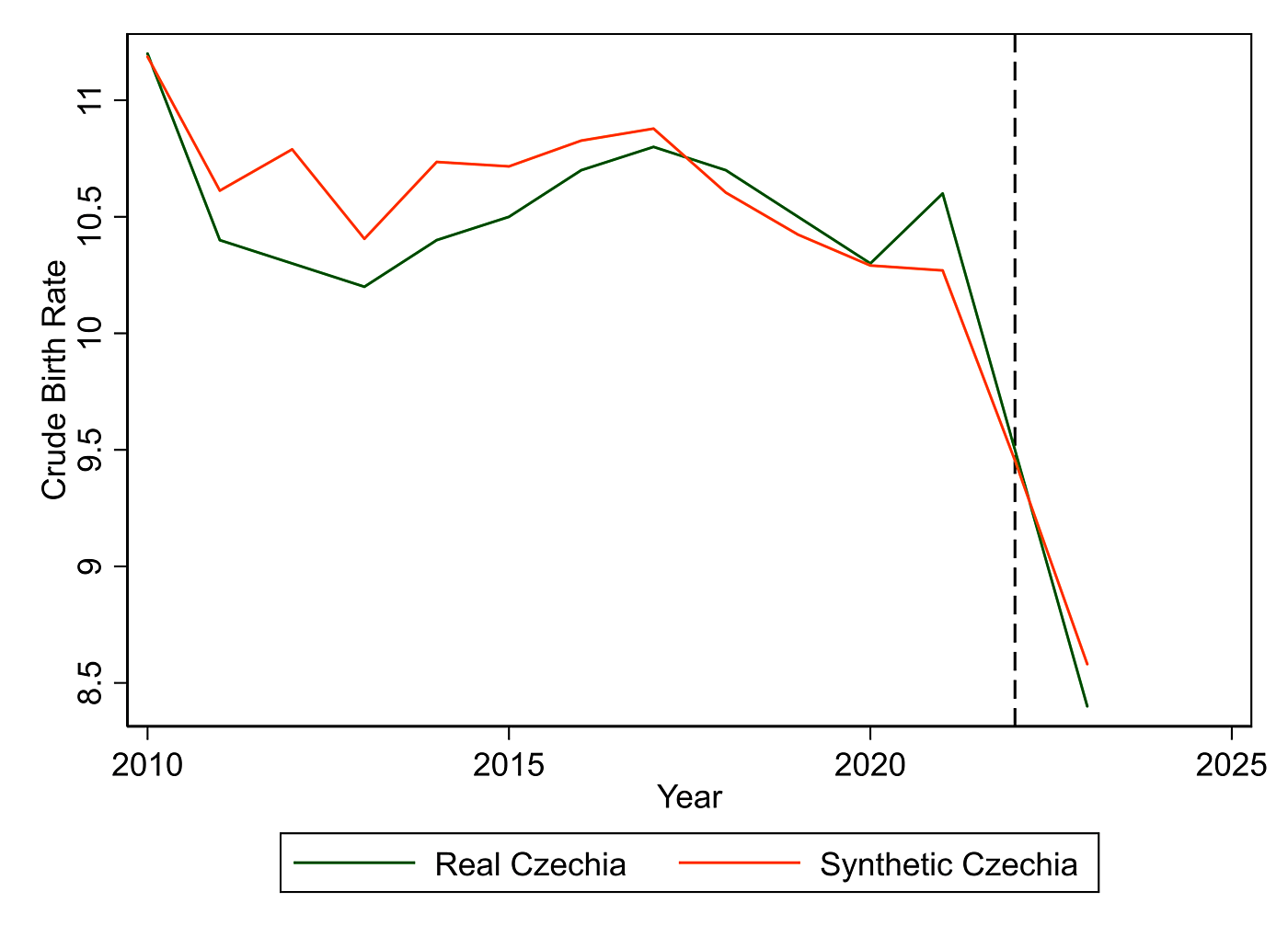

Below is a simple synthetic control model to see whether the surge of Ukrainian refugees could plausibly explain the decline in Czechia’s crude birth rate. The synthetic control method (SCM) allows us to estimate what would have happened to Czechia if a major intervention, such as a large increase in refugees, had never occurred. We can’t observe both reality and the alternative at the same time, so the SCM creates a comparison group by combining data from other places that didn’t experience the intervention. Here, that creation is called Synthetic Czechia.

Before the intervention, Synthetic Czechia is supposed to closely match Real Czechia on key indicators correlated with crude birth rates. If Synthetic Czechia well tracks Real Czechia before the refugee surge, we can trust it as a credible stand-in for what might have happened afterward without the policy. Thus, we can causally estimate whether and how much the surge of Ukrainian refugees affected crude birth rates by comparing them in Real Czechia to Synthetic Czechia.

My model constructs Synthetic Czechia from the following variables: median age, GDP per capita PPP in 2021 dollars, the total population, the population share aged 15–49, and crude birth rates with special emphasis on 2010 and 2020. All data are from the World Bank. The intervention year is 2022. The donor pool is 25 European countries where the Ukrainian refugee population is less than 1 percent of the resident population. The donor pool is restricted to Europe to better match culturally similar countries. My replication files are available upon request.

The root mean squared prediction error is 0.229 in the pre-intervention period, about 2 percent of the pre-intervention mean birth rate in Czechia. Thus, the crude birth rates in Synthetic Czechia and Real Czechia are very close in the pre-intervention period, meaning that Synthetic Czechia is a valid clone. Synthetic Czechia is a combination of Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, Switzerland, and Luxembourg in that order. That match could be better, but it’s defensible. The variables most used for constructing synthetic Czechia in the pre-intervention period are the crude birth rates and the median age, with the others accounting for less than 5 percent.

The first figure shows that there is no ocularly significant divergence in the crude birth rates between Real Czechia and Synthetic Czechia in the post-intervention period. Eyeball econometrics confirm no divergence. There is also no statistically significant divergence. That means that the SCM estimates that the surge of Ukrainian refugees had no detectable effect on crude birth rates in Czechia by 2023.

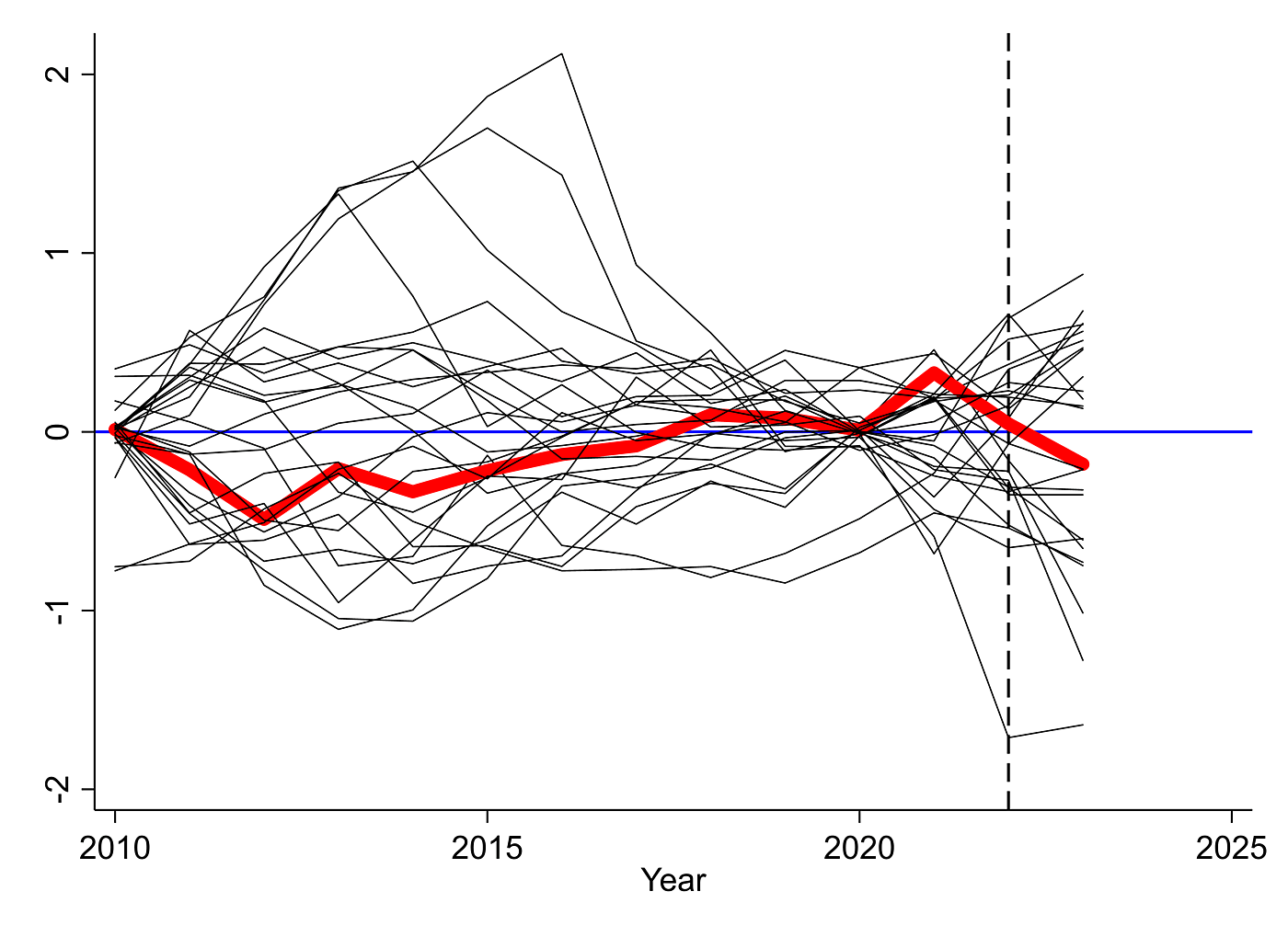

The following figure runs the above synthetic control analysis for every country in the donor pool, a robustness check called “placebo in place” to see whether any effect detected above holds. The placebo in place then plots the difference between the Synthetic and Real versions for each country. Czechia is the otherwise unremarkable thick red line in the middle of the donor pool that shows its crude birth rate isn’t much different from the donor pool countries. This robustness check is further evidence that the surge in Ukrainian refugees had no effect on the crude birth rate in Czechia.

The weakest portion of the synthetic control model above is that there is only one post-treatment year. With only one year available, the Ukrainian refugees would have to have a large and immediate fertility effect to be detected. The limited data mean that a delayed or accumulated effect would not show up. I will redo this analysis in several years when more data are available (please remind me if you don’t see it). There are more recent sources of data online, but with uncertain provenance, reliability, or availability, they show the Czechia fertility trend shown above continuing in 2024 and (so far) in 2025. Paul’s analysis also suffers from the same limited post-intervention problem, which is even more reason to highlight the same problem with my SCM.

The results of my short analysis above aren’t surprising. A good paper on immigration and fertility by Kelvin K.C. Seah used the quasi-natural experiment provided by the Mariel boatlift to plausibly estimate the effect of immigration on birth rates. He finds a temporary decline in births in Miami that affected renters more than homeowners, with rental prices as the mechanism. This isn’t surprising because immigrants affect prices for real property more than any other market. Seah concludes:

The immigration shock led to short-term declines in native childbearing activity in 1983 and 1986, although these declines were compensated by fertility increases in later years. The short-term declines in native childbearing activity after the immigration influx were possibly due to individuals delaying their childbearing plans.

Seah’s conclusions are plausible and the most defensible I’ve seen that can be gleaned from those data sources. Moving from the empirically rigorous literature to Paul’s piece reveals that his analysis is interesting but flawed. He doesn’t provide compelling evidence that Czechia’s crude birth rate fell more than other comparable countries, nor does he show that the refugees could plausibly be the cause of the statistically unremarkable absolute decline. More research must be conducted on how immigration affects fertility. It’s good that Paul looked at this issue, but his conclusion is unconvincing.