Travis Fisher

Electricity demand is growing again in America. Although many of us welcome such growth as a hopeful sign of a recovering economy, there is a new troubling debate over whether some uses of electricity are “parasitic.” Electricity policy debates have stumbled into the timeless struggle between good and evil where some are arguing that electricity should be rationed based on political “socially desirable” concerns rather than through the price system.

The poster child for politically disfavored electricity use is cryptocurrency mining. Some commenters characterize the “load” (electricity demand) from cryptocurrency mining as “parasitic,” and the White House wants to levy a high tax on its electricity use. This is a slippery slope. One person’s “parasitic load” is another’s livelihood, and it’s impossible for the government to parse the parasitic from the valuable.

Lysander Spooner’s 1875 essay Vices Are Not Crimes: A Vindication of Moral Liberty is a warning against labeling some legal uses of electricity as “parasitic.” Spooner wrote that it is “nearly impossible, in most cases, to determine what is, and what is not, vice” or “to determine where virtue ends, and vice begins.” Applying the label of virtue or vice to someone else’s electricity use is not only presumptuous and paternalistic—it is impossible because vice and virtue are unique to an individual’s circumstances.

Those who seek to reorganize the electricity sector according to the relative virtue and vice of different types of consumption should heed Spooner’s concern. If the rationing of electricity becomes driven by political determinations of parasitism, then it could be economically, socially, culturally, and politically costly for Americans without any discernible environmental benefits.

A Physical Challenge Decades in the Making

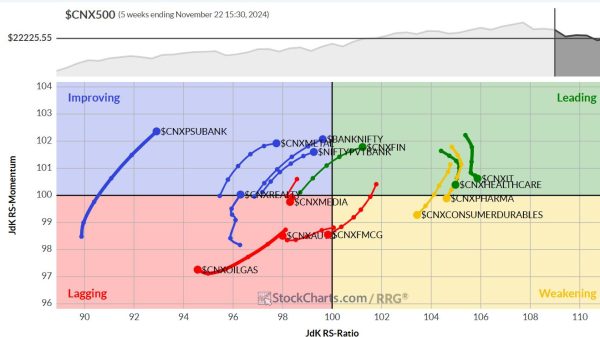

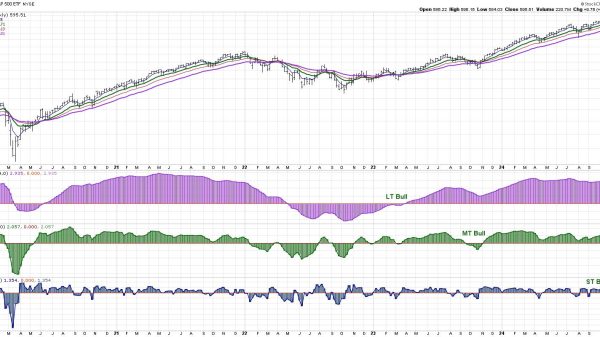

Throughout the twentieth century, electricity consumption rose steadily in the United States. In the early 2000s, however, electricity use appeared to “decouple” from economic growth. Observers credited structural shifts like increases in energy efficiency and an economy‐wide shift away from heavy industry and manufacturing toward a service economy.

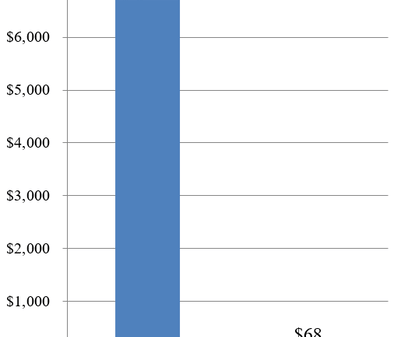

Source: page 54 here.

Today, electricity consumption is growing again, and power companies and grid operators claim that they’re not ready. Cryptocurrency mining is the politically convenient scapegoat even though its annual electricity use is only 0.6 percent to 2.3 percent of US electricity consumption.

Today’s Target: Unvirtuous “Computational Parasites”

Cryptocurrency mining’s comparatively small consumption of electricity hasn’t stopped the Biden administration from treating it like a mafia venture. In the Fiscal Year 2025 budget blueprint, President Biden again proposed a Digital Asset Mining Energy (DAME) tax, an excise tax of 30 percent applied to the electricity consumed in cryptocurrency mining. The stated reasons for the DAME tax are the White House’s concerns over greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and increased energy prices due to the recent rise in cryptocurrency mining.

However, a cryptocurrency miner doesn’t emit more GHGs through his consumption than another grid‐connected consumer who uses the same amount of energy at the same place and time, so this isn’t an issue with externalities. In fact, by using off‐peak renewable energy that would otherwise be curtailed, cryptocurrency mining is probably less GHG‐intensive than average consumption.

Another Biden‐era challenge to cryptocurrency mining came from an unlikely source—the Energy Information Administration (EIA), an independent agency within the Department of Energy. The EIA tried to require certain Bitcoin miners to disclose information about their electricity consumption. The attempt was found unlawful by the courts and retracted by the EIA, but the cryptocurrency mining community certainly heard the shot across the bow.

Some states and Canadian provinces are also debating whether to tax or restrict cryptocurrency mining. In British Columbia, new cryptocurrency mining operations are no longer allowed to connect to the power grid operated by BC Hydro. Even Texas is not immune. The state hosts about half the mining for cryptocurrencies. Austin‐based writer Russel Gold argues that crypto miners’ “gluttonous appetite is helping create an unprecedented demand for electricity.” A recent article in WIRED quotes Houston‐based energy expert Ed Hirs as likening Bitcoin miners to parasites, calling them “the tapeworm on the [Texas] grid.”

One academic paper on cryptocurrency mining in the US Pacific Northwest says “Bitcoin miners in the region should be understood as parasites on the system.” The title—and I cannot make this up—is “Computational parasites and hydropower: A political ecology of Bitcoin mining on the Columbia River.” (Screen capture included below.)

These are the seeds of political conflict. If electric utilities and their regulators can refuse service based on political goals, who gets to decide which electricity uses are politically correct? The DAME tax and the BC Hydro ban on cryptocurrency mining each set a dangerous precedent. They are a political attack on an unpopular industry that is already being held up as a scapegoat for failures to meet climate goals. For example, the “Change the Code, Not the Climate” campaign, endorsed by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D‑MA), suggests that Bitcoin should fundamentally change its business model to be more climate‐friendly.

What Could Conservatives Ration?

Now that progressives are judging the morality of electricity consumption and seeking to raise the price of electricity for unvirtuous “parasitic” industries, conservatives might follow suit. The possibilities are endless. If the next president dislikes electric vehicles, for example, perhaps there will be a moratorium on new connections for fast‐charging stations. Ditto for heat pumps, indoor grow lamps for marijuana in states that have legalized it, data centers supporting foreign‐owned websites, and the buildings of political organizations antithetical to the administration. For example, will Planned Parenthood be able to get electricity service at its next headquarters? In America, this question should be absurd.

But it’s not just the political fringe that would suffer. The impact on major industries could also be profound, and the spillover costs to American consumers could be significant. Businesses might have to ramp up political groveling just to keep the lights on. If the government can decide which electric loads are worthy, then the future of electricity‐intensive industries will depend on their connections to political power.

Conclusion

Labeling certain types of electricity consumption as “parasitic” puts us on a slippery slope. Utilities should not be forced to discriminate against some legal uses of electricity and the government should not arbitrarily raise the price of electricity for politically disfavored industries. Doing so would open up a whole new front in the culture war that will hurt everyone for no discernible benefit. Such judgments of virtue or parasitism are always in the eye of the beholder (viewed through blue‐ or red‐tinted partisan glasses). Policymakers on both sides of the aisle should recognize the danger in banning or punishing certain uses of electricity—this is an anti‐energy arms race that no one wins.