Scott Lincicome

This year, a large amount of virtual ink has been devoted to US tariff policy—and for good reason. Yet, most of this discussion has focused on the big picture—average tariff rates, big deals, and major actions or exemptions—while ignoring an issue that’s just as important, if not more so: the new tariffs’ unprecedented and, for many American businesses, crippling bureaucracy and complexity. My new column for The Dispatch digs into this growing problem and features a trove of new data demonstrating the truly radical increase in US tariff red tape—and how this byzantine new system severely burdens US companies and the economy more broadly.

As one trade compliance professional put it to Bloomberg, it’s “death by a thousand papercuts.” I count at least five reasons why.

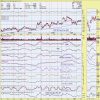

First, the legal regime for US tariffs has gone from relatively simple and straightforward to one featuring several overlapping laws, regulations, and measures. As of this week, in fact, a whopping 17 different US tariff measures and seven different legal regimes now apply to significant commercial volumes of imports into the United States—up from just three in 2017.

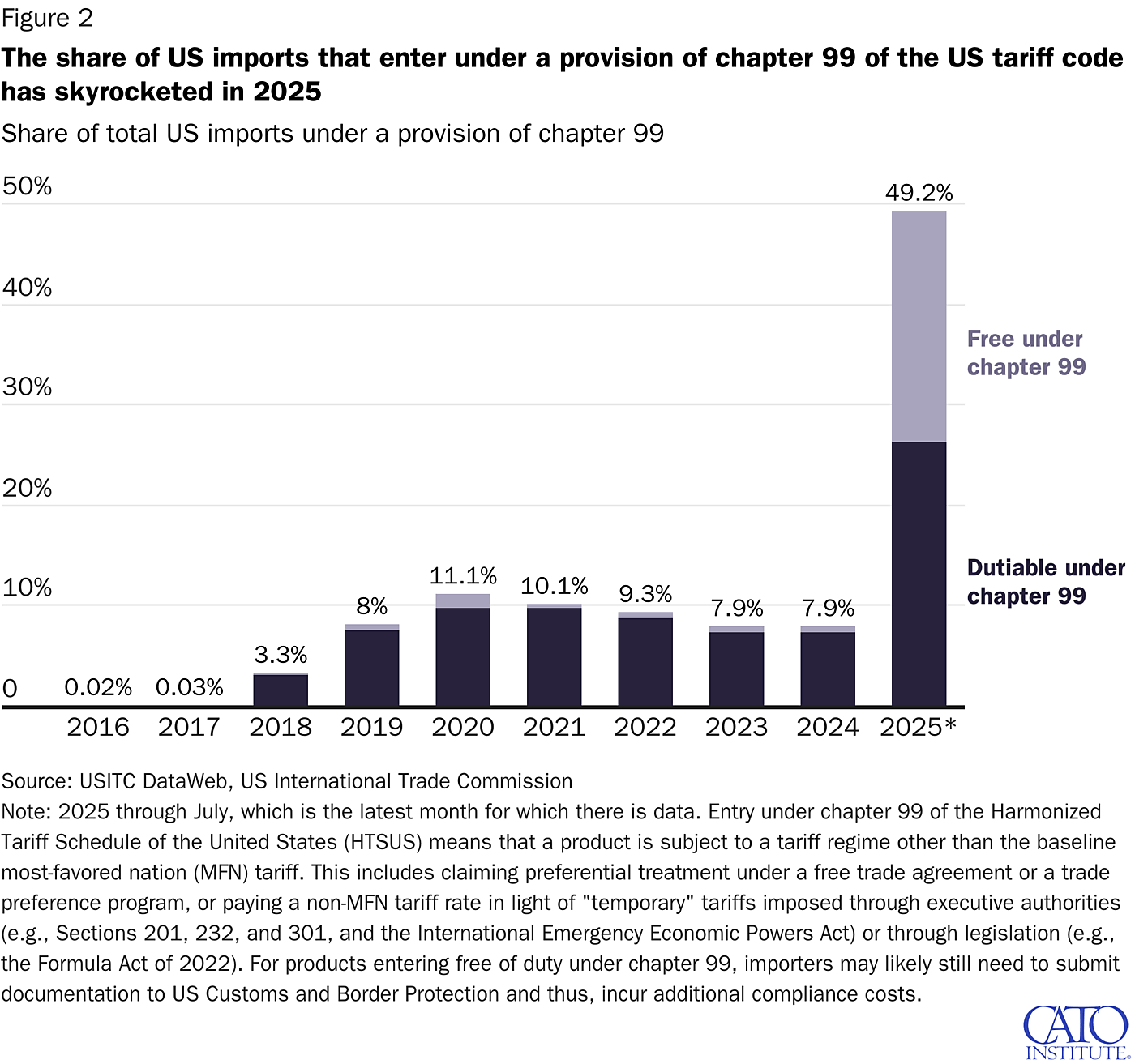

Second, the total volume of imports now subject to one or more special tariff measures (designated in Chapter 99 of the US tariff code), and thus to the new US tariff bureaucracy, went from basically nothing in 2017 to almost half of all US imports as of July of this year.

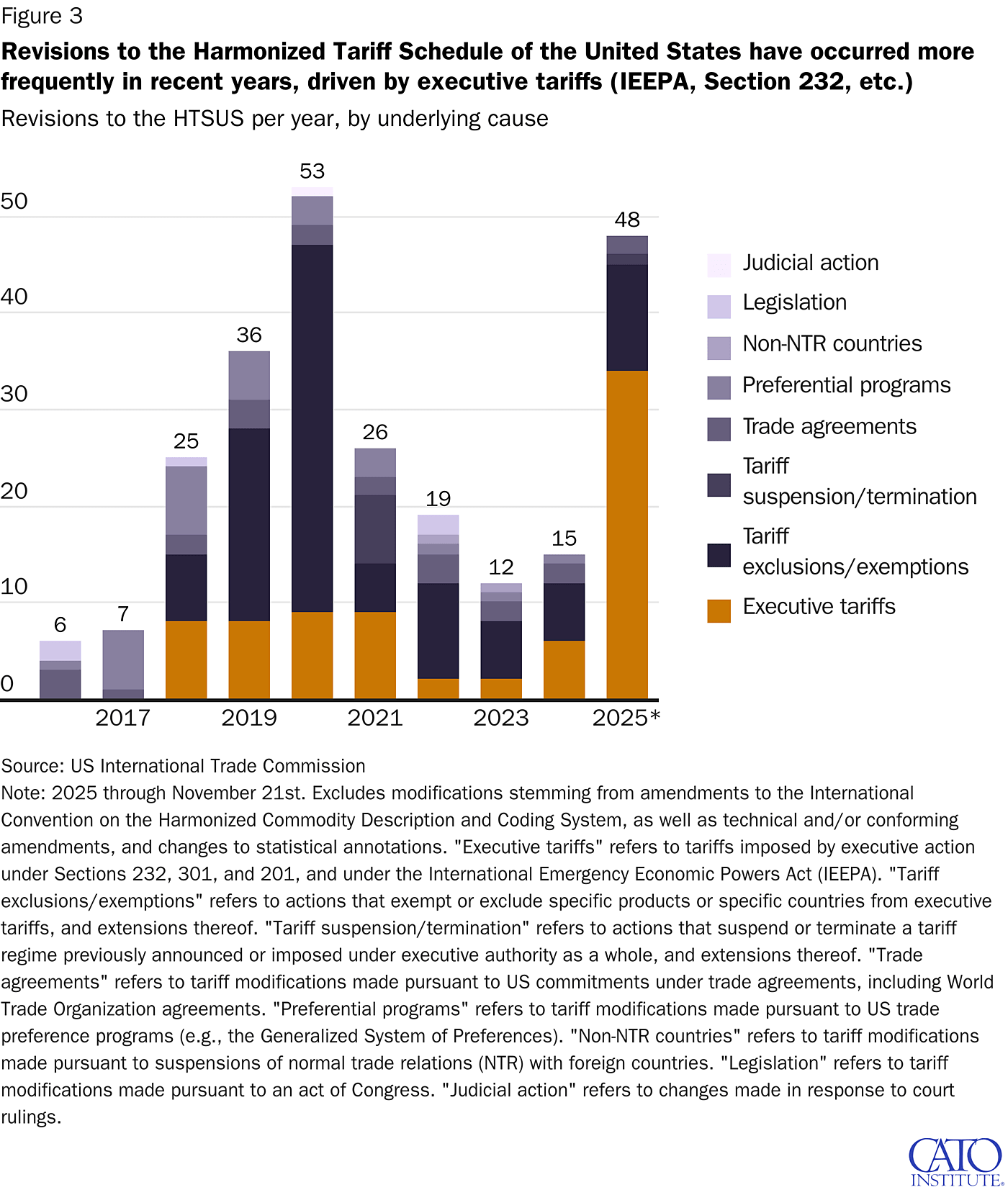

Third, another new burden for US importers is that tariff policy is now constantly changing. As the following chart shows, significant revisions to the US tariff code—both new executive branch tariffs and new exceptions to those same tariffs—have become much more frequent and economically significant (and more changes are surely on the way).

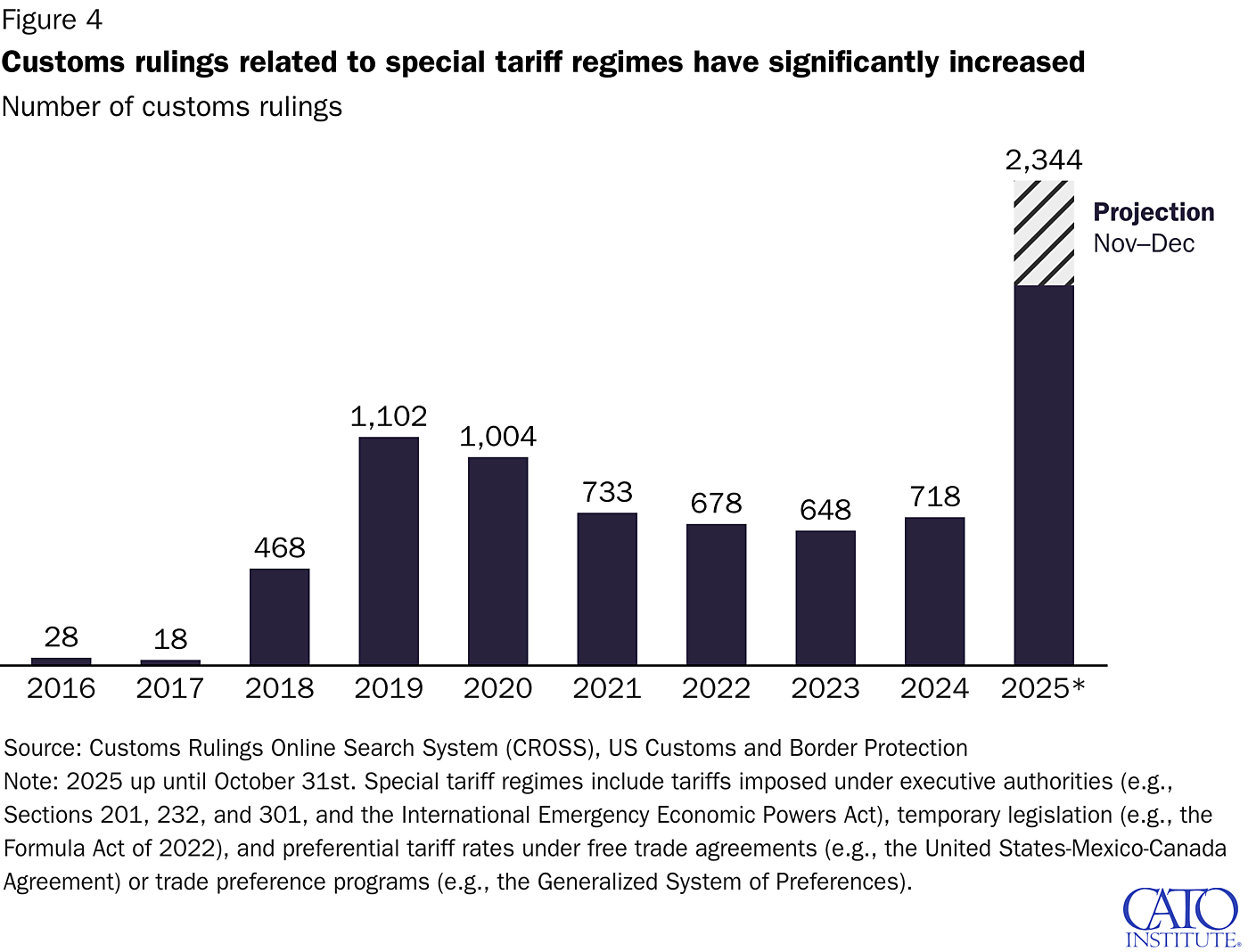

Fourth, the unprecedented and confusing changes to US tariff policy, and increased government enforcement actions against importers who make mistakes, have pushed American companies to seek official guidance from US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at an alarmingly high rate (and at a significant cost).

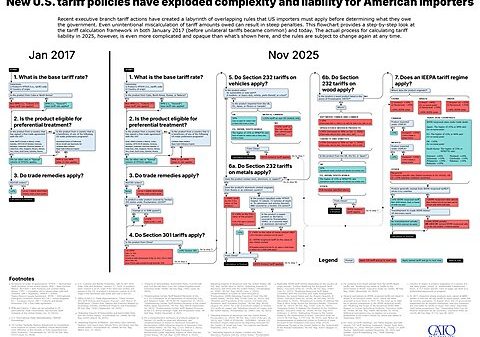

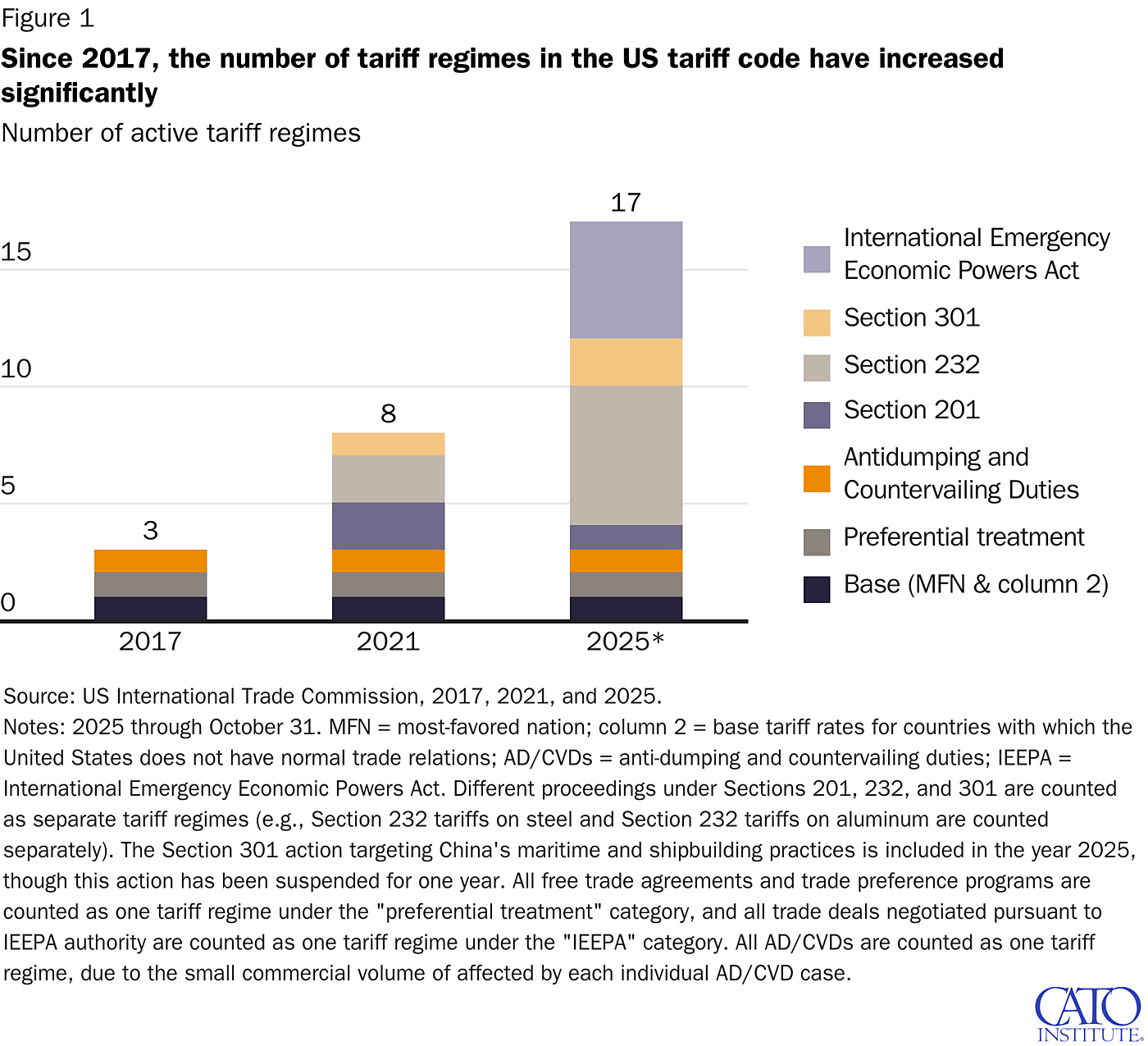

Finally, determining an importer’s total tariff liability is becoming an increasingly convoluted process—again, a radical change from the relatively simple framework of just a few years ago. The following flowchart provides a high-level summary of this process, but even it lacks several details importers would need in the real world to accurately calculate how much they owe the government. (You can download alternate versions of the flowchart: high-resolution, vertical, and PowerPoint.)

It’s thus no surprise that, as the Washington Post reports, business for customs professionals and other trade gatekeepers is “booming.”

As I discuss in my column for The Dispatch, these tariff hurdles and others similar to them have confounded US companies, seasoned trade professionals, and even CBP officials. And they’ve placed a disproportionate, if not impossible, burden on smaller American firms that lack the personnel and resources to navigate the new and sprawling tariff bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has ramped up enforcement of tariff violations, and penalties for noncompliance, even unintentional mistakes, can be significant.

The direct tax burden that President Trump’s unilateral tariffs have placed on American companies is undoubtedly significant (roughly $30 billion per month at last count). As these charts make clear, however, the tariffs’ regulatory costs are arguably even worse.